Adding Apples and Oranges¶

The saying “You can’t add apples and oranges” is one of the casual cruelties that adults unthinkingly perpetrate on children. If you asked them in the best Socratic tradition, they would have to agree that you can put two apples and three oranges into a bowl, and that this is a form of addition that is particularly natural to children. What the saying was intended to convey is that the sum

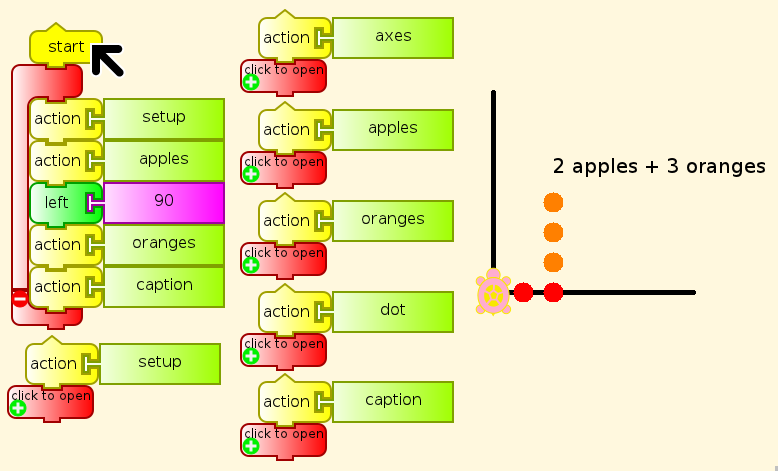

2 apples + 3 oranges

cannot be reduced or simplified to some number of apples or some number of oranges, a very different fact from what it plainly says. Now it is true that you cannot add two apples and three oranges in simple integer arithmetic, but that is only one of many kinds of arithmetic. The blanket prohibition without the context is false.

I say that this is casual, unthinking cruelty. It gets much worse when we come back to the same children years later and demand that they add x and y, in clear violation of this principle.

“Oh, but that’s not what we meant! Besides, x and y are numbers, and of course you can add numbers.”

No doubt, but it is what you said back then, with no further explanation. Now you have offered an explanation. Let us see what it explains. You say that x and y are numbers. What kind of numbers? “Well, variable numbers, of course.” I’m sorry, but that won’t do. Numbers do not vary, as children well know, even if you erroneously think you know otherwise.

Do you even know what you mean? I doubt it. The history of mathematics has many examples of people talking confidently about things they have no real understanding of, and denying the possibility of what turns out to be whole new branches of mathematics. Irrational numbers, negative numbers, imaginary numbers (notice the intended insults), non-Euclidean geometry, infinities and infinitesimals...“All right, if you’re so smart, what are variables?” Glad you asked. It is not that I am so smart, but that mathematicians share their ideas, and advance their art. Computer Scientist Ken Iverson in particular has pointed out that the function of variable names in much of mathematics and all of computer programming is the same as the function of pronouns. They are names that we can attach to something or someone temporarily in order to speak without constant repetition, and to something or someone else at any moment. Pronouns and variable names are not the same, having other purposes that do not overlap, but it is possible and even desirable to speak of variable names as pronouns in this specific context. It is even legitimate to speak of variables as pronouns, even though there is no such thing as a variable, only a variable name.

Where does Turtle Art come into this? Turtle art has variables, of course, which it calls boxes to reduce confusion, and we can name one “apples” and one “oranges”, and add them as vectors in a two-dimensional space, the TA on-screen workspace. I don’t want to take the trouble to make the turtle draw apples and oranges, so I will use colored dots instead, orange and red. (Feel free to improve on my work, as real mathematicians, artists, and so on do.) Here you go.

The idea of the box in Turtle Art is that we have a box with a name on it, and we can put a number or a bit of text inside to take out or make copies of later. This model, like the model of pronouns, provides an easy way for children to avoid being confused by adults talking in nonsensical shorthand that would require an explanation that most adults do not know how to give.